Review of “Secrets From My Tuscan Kitchen” by Judy Witts Francini

There may be no better place to read Stone’s The Agony and The Ecstasy than from an apartment with a window who’s shutters open up to a rainy sky view of the Santa Maria del Fiore Duomo in Florence.

There may be no better way to appreciate and learn Florentine cooking than from a centro storico apartment with a window that opens to reveal a view of the “San Lorenzo” Mercato Centrale so close that you can touch it, accompanied by a sparkly eyed, giggling and constantly smiling expatriate cook.

In the summer of 1991, I had the great fortune to do both in the flourishing city. I loved cooking in Italy so much that I stayed almost another five years doing it. Life moved on for me, and I haven’t been back since, though nearly daily I have thoughts of returning to this home away from home, Firenze, with a fondness that never wains.

It was with a rush of emotional recall that I tore the package from the postman’s hands emblazoned with a dozen different Certaldo postmarked Italian francobolli. No meter-read postage printout here – but works of art immortalized on a package direct from the hands of Divina Cucina.

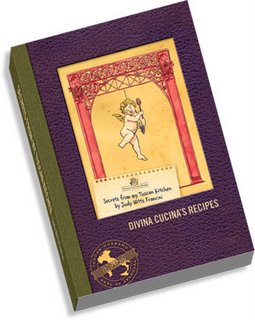

Immediately the “fatto con amore” aspects of this work struck me… even before laying eyes on the book, the choice of textured cover and interior papers was undeniably intentional. The cover art extends the texture with a visual overlay clearly intended to enhance the visceral response. Light touches of shadowing, layers, torn paper, watercolors and the “e buono!” Tuscan Husband Seal of Approval foreshadowed what would be contained. This light hearted yet purposeful design brought back the memories of Lo Scrittoio in Florence, where sketchbooks are still made one at a time entirely by hand. I’ve got my own, full of my own recipes, somewhere in my garage – but I was giving myself over to the idea that very possibly after Judy Witts Francini’s efforts to send a complete notebook – I may no longer need my own.

“Se una cosa e bella, probabilmente non e buona” – Marcella Hazan

I settled down on my own rainy-day weekend (a rarity in Santa Fe – maybe a sign sent directly from Irving Stone?) to read through this book. I’m barely one page in, just past the Baci Da Firenze, and on the next page I note this book was printed in San Gimignano – well of course, if you’re going to print an Italian book – where else. More memories begin to cascade. Then, the dedication, a barely disguised “Ti Voglio Bene” to silent, smiling partner/husband Andrea coupled with the “in love” photo on the inside back cover welcome me to begin the journey.

The rules of Judy’s kitchen are set down – shop more, cook less. Honor ingredients, keep it simple and let quality shine. Prerequisites are layed out – what you will need in your pantry (or mind) to meander through this book, and how to approach not only the ingredients, but the pace of meals & snacks throughout a Florentine’s day. I was hooked – could not stop myself and read the whole thing cover to cover in one sitting. Nearly 100 recipes, each one taking me another step across the pond and back into the fresh summer day visits to the Mercato, storytelling with friends while preparing, and then settling in after the heat of the day with a glass of wine and sumptuous food prepared easily, simply and amazingly delicious by our own hands – with guidance from a fantastic mentor.

So, I’ve got a pretty good bias going into this thing… I turn a few more pages to get to the first recipe… Fettunta. I’ll go ahead and say it – any recipe book where Fettunta is the first recipe has my vote. Pure, simple, honest and entirely dependant upon four ingredients – this is a perfect expression of the Mediterranean kitchen. I happen to like mine toasted over an open fire, and instead of cutting cloves of garlic in half, just start with the pointed end on the bread and rub it down. Hold on to the root end as the disposable handle.

“Se una cosa e bella, e buona”

– Piero Bertinotti (Ristorante Pinocchio, Borgomanero, Piatto del Buon Ricordo)

Fortunately, in Judy’s layout, along with her recipes in a hand-styled sans serif fun font, she leaves every single left hand page in the book empty, but lined for notes and with a background/heavy watermark of the Florentine lily. Perfect area for personal notes on a recipe, back-to-metric conversions (I prefer 100g pasta per person, whereas 3 oz. cuts it a little short), and variations on themes. This is a very thoughtful addition to any cookbook – it really extends the workbook sense – one could return right back to Judy and Andrea’s house and jot down notes as you learn a new recipe.

The antipasti section flows into the very next expected recipe – Crostini Toscani (called De Fegatini here) always with a smooth description of ingredients and not overly detailed, nor overly simplistic preparation description. Perhaps the highlights of all the recipes for me are reading through them to find the little nuggets of personal preference expression that Judy herself has noted. That is, there is no EXACT way to make anything – there’s at least one traditional Tuscan method, a Florentine variation, Andrea’s mother’s variation, what Judy likes, and with the open-to-scribbling facing page – an expectation that you’ll note what you like.

Two recipes in and a common American misperception is already being addressed, and I appreciate that. Though there's nothing here written about it, it's clear that this is not a health-spa, olive oil-is-god gloss over the realities of food in Italy. Butter is used just as much as olive oil, and many pedestrian American home cooks never quite understand that. There are simply some things where butter is the right fat, and others where olive oil is. It is NOT all about the olive oil, for sure. But, when olive oil is used, it's used very well - some types for cooking, some for eating raw. There are other times when butter is used - yes, either for cooking or raw. This book unabashedly acknowledges this fact by including the correct ingredients in recipes and not even bringing up anything about a fat dichotomy. Yes, Emeril, Pork Fat Rules too.

The small plates section ends with a new take on a simple old favorite – fried sage leaves with a method that stands up on their own as an appetizer, not just a forgettable garnish. Yum! Now thinking that I need to get up and walk on in to the kitchen. Instead, I get up, with the book, stumbling down the hallway and walking into doors since I can’t be bothered to look up from the book I’m reading for something as trivial as knowing where I’m walking – and decide to read the rest of the book sitting at my kitchen counter, gazing fondly at the garlic and unfiltered olive oil.

As I get settled in to reading through this book, something dawns on me, and I realize it’s because Judy put it down in writing in her forward. I’ve made a lot of these recipes and don’t recall one time being given quantities for making them. It’s part of the Italian nonna-mamma oral tradition. Some of this, more of that, ENOUGH (but NOT too much) of this, and work it until it’s just the right consistency. There’s a tactile and visual learning process that proceeds from the senses, but is not easily quantifiable by those passing the lessons along. You “just do it” and you “do it the right way” but those things are never precisely defined. That must be some of the challenge in Judy’s having set these recipes down to paper… so many of them are done by simply looking, feeling and tasting your way through them.

I realize that I’ve become engulfed in the conversion – reading this book transcends both the replicable results of measured ingredients while maintaining the sense of flexibility. So much of savory cooking NEVER depends upon precise quantities, but instead on understanding of flavor combinations, cooking techniques and desired outcomes (not to mention knowing how to compensate/convert when something inevitably does go wrong). This book consists almost entirely of recipes that could exist entirely in Mamma’s mind – and change depending on mood, season and availability of ingredients. Spend less time cooking and more time shopping indeed!

“La cosa piu importante nella vita e avere dei veri amici – pochi ma buoni”

We move into a section accurately & honestly titled “Sauces for Pasta and Other things.” Is this where I insert my emoticon? Where I pleasantly find tips on the best aglio, oglio e peperoncino, along with variations of the same – as well as Sugo di Anatra (Yum with a capital exclamation point), al’ arrabbiata, puttanesca, pesto and Salsa di Noci too! Primi piatti are where some of the shining classics of Tuscan and Florentine food come out. The beans are in here, as is the ribollita, panzanella and Pappa al pomodoro (pomorola) and of course, Pasta e Fagioli. Some unexpected surprises turn up here that I really like to see, and many of which I’m almost ready to stand up and start cooking: Tortelli di Patate, Ravioli Gnudi, Gnocchi di Patate, Polenta and all the elements of Lasagna (fresh pasta, besciamella and sugo di carne).

I find myself laughing out loud with some of the brevity of directions that are clearly saying to the readership “c’mon, we’re all adults here,” such as in the Crespelle alla Fiorentina. Where some cookbooks will go through three pages of explanation with pictures and illustrations on how hot your crepe pan needs to be, how you have to wipe it with butter, then clean it with a paper towel, how to watch the edges and top of a crepe to know when to flip it so that it’s set but not dried out, how to avoid burning your fingers, how to stack crepes so they don’t stick and don’t dry out, how much batter to use, how to spread it around the pan, etc. Divina Cucina treats us as intelligent kitchen dwellers by condensing ALL of the aforementioned tricky crepe-making aspects into two words: “Make crepes.” I love it! Thanks for treating me like a grown up, Judy. Now can I have another glass of wine before we move to the next prep item?

She closes out this section with a thinly veiled questioning of the adage that maybe one doesn’t have to be chained to the risotto pot. Risotto Divino slaps grandma in the ass deftly and ever so cleverly. You want starchy creaminess but you want to spend time talking and visiting with friends? Check.

Tuscan main courses includes grilling 101, taunting us non-Italy dwellers to visit with “The quality of meats in Tuscany does not require marinating or sauces to cover the flavor.” Overwhelming recollections of one of Judy’s fave’s that we went to, Trattoria Mario – standing room only tribute hall to the Bistecca Fiorentina bowl me over – and don’t forget the fries! Andrea’s holiday favorite of Bollito Misto (with the adults-only tip “skim the surface when needed”) and the ensuing Lesso Rifatto – yummy, oniony leftovers send messages of Italian comfort food our way. The Anatra all’arancia has me looking longingly at the oranges in my kitchen wondering if it’s OK to do duck as an Easter/Passover meal instead of lamb.

Reading through the Bollito Misto recipe, I almost miss it, but then come back and read again. There's a giveaway sign that Judy is translating from her own handwritten recipes in Italian, or that she's firmly on the other side of the fence - thinking, dreaming and creating recipes in Italian before "converting" them to English thoughts. Second sentence of the second paragraph unmistakably reads "Control the beef to see if it is cooked." Don't know about you, but this is kind of difficult in an American kitchen. On the other hand, in Italy, to controllare is to check on. Married to an Italian and living there all these years, yes, we've lost her. I check back through the book on some things I'd glossed over as possible typos and realize the same thing happened - Portions Sizes would be correct if it were Italian too. Bless you, Judy - we all want to think and dream in Italian - we just need a little more time there!

“Vivi intensamente ogni giorno della tua vita, perche ogni giorno che passa non torna piu”

Perhaps Judy’s propensity to simplify crepe-making instructions is driven by a very strong desire to make every recipe fit on one page. Clearly, multiple pages of instruction confound the intent of cooking simple food simply – and can tend to overwhelm the home cook. Keeping all recipes on one page make it easy to skim over what you’ve done and what you’ve missed; make it easy to see at-a-glance what notes you’ve written on the adjoining pages. It is with relish that I find one, and only one, recipe in the book which takes up a massive TWO pages! This is a recipe that few who read it will ever attempt. But if you’ve ever eaten this in Italy, do what you can to make it a reality – please – you’ll endlessly relive the memory and truly be thankful you went out on a limb, I promise. Cinghiale Dolce Forte is worthy of breaking the one page rule.

Though Florence is not exactly noted for it’s sea ports, Judy doesn’t shy away from the seafood dishes. Baccala alla Livornese is included, as are several fun squid, shrimp and fish dishes. We move on, the end game in play now, to Contorni, where the obligatory carciofi make several appearances as do cipollini. The personal touches inserted in recipes continue to delight, as with the explanation of why Fagioli all’uccelletto ARE for the birds. I read Piselli alla Fiorentina and have a rapid-eating-flashback trying to remember if I’ve eaten peas exactly this way – do I remember them with sugar in them? Do I need to go make a batch RIGHT NOW and see if the sensual sensations trigger state-dependent memory? I find myself wanting/wishing that this whole book was just a little more drawn out. Well, not drawn out exactly – but that we could have interspersed stories of Judy’s tours, trips and when she learned these things herself to go along with the recipes. I’m painting my own Tuscan picture in my mind as I read (and perhaps that’s the intent?), but I wouldn’t be opposed to seeing some of Judy’s painting, too. I suppose I’m framing Judy’s next book in my mind. If you’re listening Judy – I can cook, speak Italian and write – have knives (and typing skills) and will travel!

I love reading in Germana’s Fagiolini (green beans) the closing arguments to the recipe, which I simply HAVE to reprint here in their entirety:“The secret to this recipe is to use high heat and to really overcook the beans. I like to let them burn a bit, it makes them taste like Mamma made them. Most Americans like their vegetables slightly raw, but this is one recipe to try the Italian way. The beans get an almost meat like flavor that will make you wish that Germana was your Mamma too!”I think that one paragraph sums up this entire book and this author. I want more!

“Chi se fa I cazzi suoi campa cent’anni”

The last recipe in the Contorni section, Verdure Trifolate, ends with a stimulating thought “I like to puree half of the vegetables to form a creamy sauce.” Hmmm… thoughts of that unopened Xmas-gift immersion blender come to mind along with rolling out some of my own homemade saffron pappardelle or stracci. Thinking of pasta reminds of all the times throughout the book when Judy has made it clear WHEN to have cheese on your pasta and when specifically NOT to… a very important consideration when eating properly at an Italian table.

Getting on to Dolci, I begin to wax nostalgic, knowing this journey is (again) coming to an end. I read recipes for Pasta Frolla and Torta della Nonna (with a Nonno option!), and run to my own notebook to compare recipes. Unfortunately, all of mine are in grammi. I mention this to Judy on Facebook and she cheerfully intones “I’ll be happy to convert any recipe you want (back?) to grams!” The cooking-woman of the smiles is ever-present. I come across another recipe I don’t think I’ve eaten or prepared before – Frittelle di Riso, which sounds wonderful; then another one I don’t think I needed or wanted to see another recipe for (Tiramisu – sorry, though I understand your audience wants this), followed by several Siennese classics and my favorite fun dessert – Schiacchata con l’Uva – a recipe I’m sure was created in order to get Tuscan kids into the kitchen. I’m pleased to see that just a couple of bread recipes are included at the end – along with a clear explanation of why Tuscan bread is intentionally not salted (so many leftover recipes require stable stale bread – only possible without salt).

The train pulls out of the station with Cecina, a recipe index and the aforementioned Innamorata and I’m waving and weaping. At the same time, my own son, Adensunset, 7 years old is tugging on my sleeve “Dad, I’m hungry AND bored – can’t we cook something?” I answer “Well sure, dude, have you ever seen FRIED cookies with zigzag edges with their tails pulled through a hole in the middle?” Divina Cucina has, and it’s on page 187. After that, we might have to run to the store to see if there’s any duck. If not, we’ll just have to get the wild boar.

20 Euros + about 10 for shipping http://divinacucina.com/code/secrets.html

There may be no better way to appreciate and learn Florentine cooking than from a centro storico apartment with a window that opens to reveal a view of the “San Lorenzo” Mercato Centrale so close that you can touch it, accompanied by a sparkly eyed, giggling and constantly smiling expatriate cook.

In the summer of 1991, I had the great fortune to do both in the flourishing city. I loved cooking in Italy so much that I stayed almost another five years doing it. Life moved on for me, and I haven’t been back since, though nearly daily I have thoughts of returning to this home away from home, Firenze, with a fondness that never wains.

It was with a rush of emotional recall that I tore the package from the postman’s hands emblazoned with a dozen different Certaldo postmarked Italian francobolli. No meter-read postage printout here – but works of art immortalized on a package direct from the hands of Divina Cucina.

Immediately the “fatto con amore” aspects of this work struck me… even before laying eyes on the book, the choice of textured cover and interior papers was undeniably intentional. The cover art extends the texture with a visual overlay clearly intended to enhance the visceral response. Light touches of shadowing, layers, torn paper, watercolors and the “e buono!” Tuscan Husband Seal of Approval foreshadowed what would be contained. This light hearted yet purposeful design brought back the memories of Lo Scrittoio in Florence, where sketchbooks are still made one at a time entirely by hand. I’ve got my own, full of my own recipes, somewhere in my garage – but I was giving myself over to the idea that very possibly after Judy Witts Francini’s efforts to send a complete notebook – I may no longer need my own.

“Se una cosa e bella, probabilmente non e buona” – Marcella Hazan

I settled down on my own rainy-day weekend (a rarity in Santa Fe – maybe a sign sent directly from Irving Stone?) to read through this book. I’m barely one page in, just past the Baci Da Firenze, and on the next page I note this book was printed in San Gimignano – well of course, if you’re going to print an Italian book – where else. More memories begin to cascade. Then, the dedication, a barely disguised “Ti Voglio Bene” to silent, smiling partner/husband Andrea coupled with the “in love” photo on the inside back cover welcome me to begin the journey.

The rules of Judy’s kitchen are set down – shop more, cook less. Honor ingredients, keep it simple and let quality shine. Prerequisites are layed out – what you will need in your pantry (or mind) to meander through this book, and how to approach not only the ingredients, but the pace of meals & snacks throughout a Florentine’s day. I was hooked – could not stop myself and read the whole thing cover to cover in one sitting. Nearly 100 recipes, each one taking me another step across the pond and back into the fresh summer day visits to the Mercato, storytelling with friends while preparing, and then settling in after the heat of the day with a glass of wine and sumptuous food prepared easily, simply and amazingly delicious by our own hands – with guidance from a fantastic mentor.

So, I’ve got a pretty good bias going into this thing… I turn a few more pages to get to the first recipe… Fettunta. I’ll go ahead and say it – any recipe book where Fettunta is the first recipe has my vote. Pure, simple, honest and entirely dependant upon four ingredients – this is a perfect expression of the Mediterranean kitchen. I happen to like mine toasted over an open fire, and instead of cutting cloves of garlic in half, just start with the pointed end on the bread and rub it down. Hold on to the root end as the disposable handle.

“Se una cosa e bella, e buona”

– Piero Bertinotti (Ristorante Pinocchio, Borgomanero, Piatto del Buon Ricordo)

Fortunately, in Judy’s layout, along with her recipes in a hand-styled sans serif fun font, she leaves every single left hand page in the book empty, but lined for notes and with a background/heavy watermark of the Florentine lily. Perfect area for personal notes on a recipe, back-to-metric conversions (I prefer 100g pasta per person, whereas 3 oz. cuts it a little short), and variations on themes. This is a very thoughtful addition to any cookbook – it really extends the workbook sense – one could return right back to Judy and Andrea’s house and jot down notes as you learn a new recipe.

The antipasti section flows into the very next expected recipe – Crostini Toscani (called De Fegatini here) always with a smooth description of ingredients and not overly detailed, nor overly simplistic preparation description. Perhaps the highlights of all the recipes for me are reading through them to find the little nuggets of personal preference expression that Judy herself has noted. That is, there is no EXACT way to make anything – there’s at least one traditional Tuscan method, a Florentine variation, Andrea’s mother’s variation, what Judy likes, and with the open-to-scribbling facing page – an expectation that you’ll note what you like.

Two recipes in and a common American misperception is already being addressed, and I appreciate that. Though there's nothing here written about it, it's clear that this is not a health-spa, olive oil-is-god gloss over the realities of food in Italy. Butter is used just as much as olive oil, and many pedestrian American home cooks never quite understand that. There are simply some things where butter is the right fat, and others where olive oil is. It is NOT all about the olive oil, for sure. But, when olive oil is used, it's used very well - some types for cooking, some for eating raw. There are other times when butter is used - yes, either for cooking or raw. This book unabashedly acknowledges this fact by including the correct ingredients in recipes and not even bringing up anything about a fat dichotomy. Yes, Emeril, Pork Fat Rules too.

The small plates section ends with a new take on a simple old favorite – fried sage leaves with a method that stands up on their own as an appetizer, not just a forgettable garnish. Yum! Now thinking that I need to get up and walk on in to the kitchen. Instead, I get up, with the book, stumbling down the hallway and walking into doors since I can’t be bothered to look up from the book I’m reading for something as trivial as knowing where I’m walking – and decide to read the rest of the book sitting at my kitchen counter, gazing fondly at the garlic and unfiltered olive oil.

As I get settled in to reading through this book, something dawns on me, and I realize it’s because Judy put it down in writing in her forward. I’ve made a lot of these recipes and don’t recall one time being given quantities for making them. It’s part of the Italian nonna-mamma oral tradition. Some of this, more of that, ENOUGH (but NOT too much) of this, and work it until it’s just the right consistency. There’s a tactile and visual learning process that proceeds from the senses, but is not easily quantifiable by those passing the lessons along. You “just do it” and you “do it the right way” but those things are never precisely defined. That must be some of the challenge in Judy’s having set these recipes down to paper… so many of them are done by simply looking, feeling and tasting your way through them.

I realize that I’ve become engulfed in the conversion – reading this book transcends both the replicable results of measured ingredients while maintaining the sense of flexibility. So much of savory cooking NEVER depends upon precise quantities, but instead on understanding of flavor combinations, cooking techniques and desired outcomes (not to mention knowing how to compensate/convert when something inevitably does go wrong). This book consists almost entirely of recipes that could exist entirely in Mamma’s mind – and change depending on mood, season and availability of ingredients. Spend less time cooking and more time shopping indeed!

“La cosa piu importante nella vita e avere dei veri amici – pochi ma buoni”

We move into a section accurately & honestly titled “Sauces for Pasta and Other things.” Is this where I insert my emoticon? Where I pleasantly find tips on the best aglio, oglio e peperoncino, along with variations of the same – as well as Sugo di Anatra (Yum with a capital exclamation point), al’ arrabbiata, puttanesca, pesto and Salsa di Noci too! Primi piatti are where some of the shining classics of Tuscan and Florentine food come out. The beans are in here, as is the ribollita, panzanella and Pappa al pomodoro (pomorola) and of course, Pasta e Fagioli. Some unexpected surprises turn up here that I really like to see, and many of which I’m almost ready to stand up and start cooking: Tortelli di Patate, Ravioli Gnudi, Gnocchi di Patate, Polenta and all the elements of Lasagna (fresh pasta, besciamella and sugo di carne).

I find myself laughing out loud with some of the brevity of directions that are clearly saying to the readership “c’mon, we’re all adults here,” such as in the Crespelle alla Fiorentina. Where some cookbooks will go through three pages of explanation with pictures and illustrations on how hot your crepe pan needs to be, how you have to wipe it with butter, then clean it with a paper towel, how to watch the edges and top of a crepe to know when to flip it so that it’s set but not dried out, how to avoid burning your fingers, how to stack crepes so they don’t stick and don’t dry out, how much batter to use, how to spread it around the pan, etc. Divina Cucina treats us as intelligent kitchen dwellers by condensing ALL of the aforementioned tricky crepe-making aspects into two words: “Make crepes.” I love it! Thanks for treating me like a grown up, Judy. Now can I have another glass of wine before we move to the next prep item?

She closes out this section with a thinly veiled questioning of the adage that maybe one doesn’t have to be chained to the risotto pot. Risotto Divino slaps grandma in the ass deftly and ever so cleverly. You want starchy creaminess but you want to spend time talking and visiting with friends? Check.

Tuscan main courses includes grilling 101, taunting us non-Italy dwellers to visit with “The quality of meats in Tuscany does not require marinating or sauces to cover the flavor.” Overwhelming recollections of one of Judy’s fave’s that we went to, Trattoria Mario – standing room only tribute hall to the Bistecca Fiorentina bowl me over – and don’t forget the fries! Andrea’s holiday favorite of Bollito Misto (with the adults-only tip “skim the surface when needed”) and the ensuing Lesso Rifatto – yummy, oniony leftovers send messages of Italian comfort food our way. The Anatra all’arancia has me looking longingly at the oranges in my kitchen wondering if it’s OK to do duck as an Easter/Passover meal instead of lamb.

Reading through the Bollito Misto recipe, I almost miss it, but then come back and read again. There's a giveaway sign that Judy is translating from her own handwritten recipes in Italian, or that she's firmly on the other side of the fence - thinking, dreaming and creating recipes in Italian before "converting" them to English thoughts. Second sentence of the second paragraph unmistakably reads "Control the beef to see if it is cooked." Don't know about you, but this is kind of difficult in an American kitchen. On the other hand, in Italy, to controllare is to check on. Married to an Italian and living there all these years, yes, we've lost her. I check back through the book on some things I'd glossed over as possible typos and realize the same thing happened - Portions Sizes would be correct if it were Italian too. Bless you, Judy - we all want to think and dream in Italian - we just need a little more time there!

“Vivi intensamente ogni giorno della tua vita, perche ogni giorno che passa non torna piu”

Perhaps Judy’s propensity to simplify crepe-making instructions is driven by a very strong desire to make every recipe fit on one page. Clearly, multiple pages of instruction confound the intent of cooking simple food simply – and can tend to overwhelm the home cook. Keeping all recipes on one page make it easy to skim over what you’ve done and what you’ve missed; make it easy to see at-a-glance what notes you’ve written on the adjoining pages. It is with relish that I find one, and only one, recipe in the book which takes up a massive TWO pages! This is a recipe that few who read it will ever attempt. But if you’ve ever eaten this in Italy, do what you can to make it a reality – please – you’ll endlessly relive the memory and truly be thankful you went out on a limb, I promise. Cinghiale Dolce Forte is worthy of breaking the one page rule.

Though Florence is not exactly noted for it’s sea ports, Judy doesn’t shy away from the seafood dishes. Baccala alla Livornese is included, as are several fun squid, shrimp and fish dishes. We move on, the end game in play now, to Contorni, where the obligatory carciofi make several appearances as do cipollini. The personal touches inserted in recipes continue to delight, as with the explanation of why Fagioli all’uccelletto ARE for the birds. I read Piselli alla Fiorentina and have a rapid-eating-flashback trying to remember if I’ve eaten peas exactly this way – do I remember them with sugar in them? Do I need to go make a batch RIGHT NOW and see if the sensual sensations trigger state-dependent memory? I find myself wanting/wishing that this whole book was just a little more drawn out. Well, not drawn out exactly – but that we could have interspersed stories of Judy’s tours, trips and when she learned these things herself to go along with the recipes. I’m painting my own Tuscan picture in my mind as I read (and perhaps that’s the intent?), but I wouldn’t be opposed to seeing some of Judy’s painting, too. I suppose I’m framing Judy’s next book in my mind. If you’re listening Judy – I can cook, speak Italian and write – have knives (and typing skills) and will travel!

I love reading in Germana’s Fagiolini (green beans) the closing arguments to the recipe, which I simply HAVE to reprint here in their entirety:“The secret to this recipe is to use high heat and to really overcook the beans. I like to let them burn a bit, it makes them taste like Mamma made them. Most Americans like their vegetables slightly raw, but this is one recipe to try the Italian way. The beans get an almost meat like flavor that will make you wish that Germana was your Mamma too!”I think that one paragraph sums up this entire book and this author. I want more!

“Chi se fa I cazzi suoi campa cent’anni”

The last recipe in the Contorni section, Verdure Trifolate, ends with a stimulating thought “I like to puree half of the vegetables to form a creamy sauce.” Hmmm… thoughts of that unopened Xmas-gift immersion blender come to mind along with rolling out some of my own homemade saffron pappardelle or stracci. Thinking of pasta reminds of all the times throughout the book when Judy has made it clear WHEN to have cheese on your pasta and when specifically NOT to… a very important consideration when eating properly at an Italian table.

Getting on to Dolci, I begin to wax nostalgic, knowing this journey is (again) coming to an end. I read recipes for Pasta Frolla and Torta della Nonna (with a Nonno option!), and run to my own notebook to compare recipes. Unfortunately, all of mine are in grammi. I mention this to Judy on Facebook and she cheerfully intones “I’ll be happy to convert any recipe you want (back?) to grams!” The cooking-woman of the smiles is ever-present. I come across another recipe I don’t think I’ve eaten or prepared before – Frittelle di Riso, which sounds wonderful; then another one I don’t think I needed or wanted to see another recipe for (Tiramisu – sorry, though I understand your audience wants this), followed by several Siennese classics and my favorite fun dessert – Schiacchata con l’Uva – a recipe I’m sure was created in order to get Tuscan kids into the kitchen. I’m pleased to see that just a couple of bread recipes are included at the end – along with a clear explanation of why Tuscan bread is intentionally not salted (so many leftover recipes require stable stale bread – only possible without salt).

The train pulls out of the station with Cecina, a recipe index and the aforementioned Innamorata and I’m waving and weaping. At the same time, my own son, Adensunset, 7 years old is tugging on my sleeve “Dad, I’m hungry AND bored – can’t we cook something?” I answer “Well sure, dude, have you ever seen FRIED cookies with zigzag edges with their tails pulled through a hole in the middle?” Divina Cucina has, and it’s on page 187. After that, we might have to run to the store to see if there’s any duck. If not, we’ll just have to get the wild boar.

20 Euros + about 10 for shipping http://divinacucina.com/code/secrets.html

Labels: Italian cooking recipes cookbooks Italy Florence Firenze Divina Cucina cooking classes judy witts

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home